Stephen Chundama and Sweta Saxena

The global community embarked on an ambitious, yet manageable, 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015. The year 2023 marks its mid-point and is also a wakeup call to African leaders – inadequate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) reveals that the continent will not achieve the SDGs without urgent and decisive actions at all levels of global, regional and national leadership.

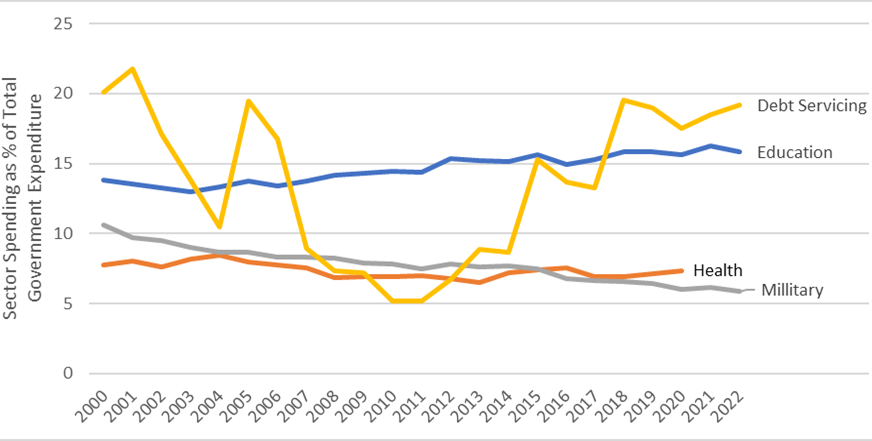

It is obvious that the confluence of crises (including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine war, climate change) have set the 2030 Agenda back. The pandemic alone produced 62 million new poor people in Africa in 2021 and revealed the existing inequities between the formal and informal labor markets, urban and rural areas, and men and women. To fight these recent crises, countries used up all their fiscal ammunition leading to what can only be termed as the Sovereign Debt Crisis. Indeed, 24 of Africa's 35 low-income countries are in or at high risk of debt distress with the continent owing over USD 650 billion in external debt and USD 69 billion in debt repayments this year. The cost of this debt crisis is visible in leaving the social sectors behind – whereby debt service occupies a higher share of government spending compared to spending on education (SDG4) and health (SDG3) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Sector Spending as % of Total Government Expenditure (2000 – 2022)

Impact of debt on Education sector development

Even after signing the Paris Declaration (2021) and committing to allocate at least 4-6 percent of GDP or 15-20 percent of total public expenditure to education, Africa has marginally satisfied these requirements since 2015. This is despite the state of education systems and infrastructure that lags far behind the rest of the world. Therefore, it is reasonable to interpret the 15.8 percent (figure 1) allocated to education in 2022 with “a pinch of salt” since budgeted amounts seldom translate in the same amounts being disbursed and used for their intended purposes.

Impact of debt on Health sector development

With health systems and infrastructure in Africa failing to cope with the historically high morbidity and mortality rates due to the continent’s high disease burden, African countries signed the Abuja Declaration (2001), committing to allocate at least 15 percent of their budgets to health spending. However, since its adoption in 2001, most countries have failed to meet their obligations under the Declaration, with countries in or at risk of debt distress allocating an average of 7.3 percent to the health sector in 2020.

Are the priorities of Governments in the right place?

Despite limited resources, African countries in or at risk of debt distress on average spend about 6 percent (figure 1) of their budgets on military, even when the vast majority of the continent enjoys relative peace. Granted, there has been a steady decline in military spending since 2000, a 6 percent allocation is too high and is about the same as what they allocate to social security[1] and almost the same as what is spent on the health sector. This calls for reprioritization of expenditures.

What needs to be done?

There needs to be a global acknowledgement by means of a political declaration that the current debt crisis in Africa is an international disaster and the solution must be based on consensus, multilateralism, and inclusivity of all parties involved, beyond the mechanism of the G20 Common Framework. This global support may provide the impetus for efforts, such as the Bridgetown Initiative 2.0, that are aimed at debt forgiveness and restructuring through the provision of immediate liquidity support (including the SDG Stimulus) and restoration of debt sustainability.

Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged that the global financial architecture (GFA) is not fit for purpose and must be reformed to enhance access by African countries to larger amounts of concessional debt through the establishment of an inclusive and equitable global economic governance system, as espoused in Our Common Agenda. The reform of the GFA must ensure that the risk premium for African debt is fairly determined and must provide for the overhaul of the Low-Income Countries Debt Sustainability Framework into one that offers sufficient early warning to countries and is better aligned to the SDGs. Also, regional Development Finance Institutions need to assume greater responsibility in the continent’s development by expanding the scope of their finance to support African governments in fulfilling their social contracts to their citizens through the provision of social services and infrastructure.

At the national level, governments must strengthen their governance systems, and prioritize high impact, sustainable public investments when allocating scarce resources. These measures should be coupled with interventions aimed at enhancing domestic resource mobilization, such as broadening their tax bases by formalizing businesses, enhancing tax administration/compliance, as well as sealing leakages related to illicit financial flows.

Without the full recognition of the impact of sovereign debt on Africa’s developmental aspirations, it is hard to fathom pathways leading to the successful completion of Agendas 2030 and 2063.

[1] African countries allocate 2.2 percent of GDP to social spending on vulnerable groups according to ILO | Social Protection Platform (social-protection.org). African countries in or at risk of desk distress are estimated to spend about 6 percent of total government expenditure on vulnerable groups such as old people.