Introduction

For a growing number of consumers, the true cost of a product goes far beyond its price tag. Driven by deep concerns over climate change and social equity, and aware that every purchase contributes to a collective impact, they are keen to know the story behind their products—from carbon footprint to labor practices. This increasing consumer awareness is driving demand for ethical, eco-friendly products and pressuring companies to adopt sustainable practices.

The Role of Sustainability Standards

This is where sustainability standards become essential; they set clear environmental, social, and economic requirements for companies.[i] When a company complies with these standards, it is issued with a certificate by an accredited conformity assessment body and allowed to use a label on its products to signify compliance with the sustainability standards. This label acts as credible proof for consumers that the product was made sustainably. In global value chains, where raw materials and components cross multiple borders before becoming finished goods, such certifications help verify sustainability at every step.[ii]

Beyond consumer pressure, a new layer of regulatory enforcement is making sustainability a hard law requirement. Market access is increasingly contingent on meeting strict and legally binding environmental and ethical criteria. Some countries/regions have incorporated sustainability standards by referencing them in regulations that determine market access. For instance, the Republic of Korea (one of the world’s top ten timber consumers) has embedded sustainability standards into its regulatory framework to combat illegal deforestation and keep illegally harvested timber off its domestic market. Its Detailed Standards for Determining the Legality of Imported Timber and Timber Products accompanying the Act on the Sustainable Use of Timbers explicitly recognizes sustainability standards as proof of compliance with timber legality requirements.

Global Challenges, Local Realities

Most sustainability standards in use today originate from non-governmental organizations (e.g., Fairtrade International, the Aquaculture Stewardship Council [ASC] and the Rainforest Alliance) and private sector initiatives (e.g., GLOBALG.A.P.). While these standards are vital for sustainable global production, their top-down approach often creates significant hurdles for producers in developing countries. These countries are seldom involved in developing the very standards they are expected to follow. As a result, there is often a disconnect between the standards’ requirements and the practical realities on the ground, as they tend to fail to account for regional environmental, economic, or social contexts.[iii]

For example, Indonesia and Malaysia —the world’s largest producers of palm oil— created their own Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Malaysia Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standards. This was largely because smallholder producers, who make up a significant portion of palm oil production, were being marginalized by the globally recognized Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). RSPO certifications were mainly going to large, listed companies accessing the European market. The ISPO and MSPO, being more aligned with the local context while still satisfying international expectations for sustainability, have been effective in supplying lower-priced sustainable palm oil to emerging markets like China and India. These markets account for a large share of the global palm oil market and are less focused on specific high-cost certifications like RSPO.[iv] Similarly, in May 2025, the Kenyan government suspended Rainforest Alliance certification for tea factories due to the financial strain on smallholder producers who saw little return.[v]

The Eco-Mark Africa Ecolabelling Scheme

Recognizing these challenges, African policymakers have long advocated for inclusive and regionally responsive approach to sustainability standards. A pivotal 2008 resolution from the 12th session of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment “called upon the Commission of the African Union, Governments and all stakeholders to work together to ensure the development and implementation of an African ecolabelling mechanism based on African experiences and lessons”.[vi] Consequently, the African Organization for Standardisation (ARSO) launched the Eco-Mark Africa ecolabelling scheme (previously known as the African Ecolabelling Mechanism). It is Africa’s first continental certification mark, awarded to goods and services produced sustainably. It is also a registered trademark in World Intellectual Property Organization, European Union Intellectual Property Office and the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office.

Under this scheme, four sustainability standards (on agriculture, fisheries, forestry and tourism) were published in 2014, followed by two standards (on tilapia and the African catfish) in 2018. More recently, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) supported ARSO to expand the scheme’s scope. New standards have been developed covering vital sectors including sustainable leather and footwear, sustainable textile, sustainable fashion, sustainable criteria for mining, sustainable criteria for natural building stone production, sustainable criteria for sand mining, sustainable cotton, green building and construction, tourism accommodation facilities and tourism destination classification. These standards, developed in line with the international principles of standardization[vii], were approved by the ARSO Council in June 2025. This paves the way for them to be implemented by private sector players interested in acquiring the certifications due to the related benefits.

Unlike most existing ecolabelling schemes that offer a single, all-or-nothing certification, Eco-Mark Africa introduces a progressive, four-tiered system: Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum. This tiered model is particularly beneficial for Africa’s landscape of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs and MSMEs). It enables businesses to start with a more attainable Bronze certification and gradually move up the ladder, reducing the burden of high upfront compliance costs.

The system is designed to encourage continuous improvement. Bronze and Silver certifications serve as transitional stages, valid for one and two years respectively, after which companies must progress to higher tiers. Firms that already meet high sustainability benchmarks can directly pursue Gold or Platinum certification, which are renewable every three years.

Though still in its early stages, this flexible and inclusive approach holds promise—but further research will be important to assess its real-world impact on market access and sustainability outcomes.

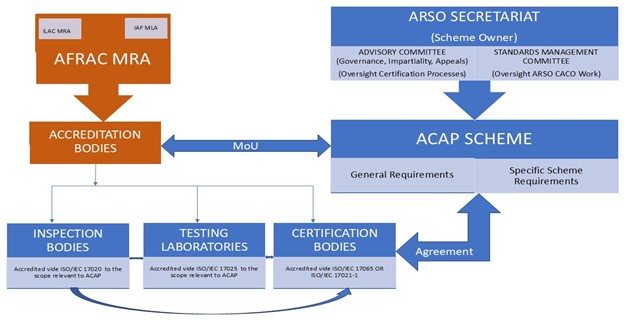

To preserve its international standing, Eco-Mark Africa operates under two complementary frameworks i.e., ISO/IEC 17065, the worldwide standard for bodies certifying products, processes and services, and ARSO’s African Conformity Assessment Program (ACAP) which provide guidelines and requirements for implementation and management of certification schemes. Moreover, ARSO works with accreditation bodies of Member States which are recognized by the African Accreditation Cooperation (AFRAC) and are affiliated with the International Accreditation Forum (IAF) to assess the competence of certification bodies to carry out audits for Eco-Mark Africa’s certification scheme.

Currently, ARSO has established memorandum of understandings with the Kenya Accreditation Service (KENAS), the Egyptian Accreditation Council (EGAC) and the South African Development Community Accreditation Service (SADCAS) to assess certification bodies (see Figure 1 below). Engagements are also underway with national accreditation bodies of Ethiopia, Mauritius, Nigeria, South Africa and Tunisia.

With support from ECA, national conformity assessment bodies in Kenya and Zambia have already been accredited and licensed to issue Eco-Mark certificates. Additional national standardization bodies in Botswana, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Togo and Zimbabwe have expressed interest in the scheme and engagements are ongoing to ensure they are accredited and licensed. This expanding network is critical in ensuring accessibility to conformity bodies by companies across the continent.

Conclusion

In today’s global economy, sustainability is no longer a niche preference; it is becoming a fundamental requirement. For African businesses (especially the SMEs/MSMEs), Eco-Mark Africa offers a vital solution. It enables them to meet international sustainability requirements while addressing local realities. Benchmarking studies reveal that Eco-Mark Africa’s standards not only align with, but in some cases outperform existing global sustainability frameworks. Preliminary assessments by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) confirm strong alignment with key regulations like the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), Environment, Social & Governance (ESG) framework and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDD). This positions Eco-Mark Africa certification as a potentially powerful one-stop compliance instrument for a variety of current and emerging regulatory requirements.

For these sustainability standards to drive real and impactful change, widespread adoption is paramount. Some private sector dealers have already expressed interest in the Eco-Mark Africa sustainability standards. However, as a relatively new initiative, Eco-Mark Africa requires greater awareness, capacity-building, and strategic partnerships to scale its reach. To promote global recognition, engagement with key target markets such as the European Union, as well as internationally recognized accreditation bodies will be critical. Moreover, government support through policies like sustainable public procurement, export incentives, and green industrial strategies could significantly accelerate its uptake.

By embracing homegrown standards like Eco-Mark Africa, the continent can ensure that its producers are not just participants in the global sustainability movement—but are leading it.

Figure 1 — The ARSO Conformity Assessment Programme Structure

*Laura Naliaka is a Trade Policy Expert at UNECA’s Africa Trade Policy Centre and Reuben Gisore is the Technical Director at the African Organization for Standardization

[i] The United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards (UNFSS, 2013) defines sustainability standards as standards specifying requirements that producers, traders, manufacturers, retailers or service providers may be asked to meet, relating to a wide range of sustainability metrics, including respect for basic human rights, worker health and safety, the environmental impacts of production, community relations, land use planning and others.

[ii] UNCTAD. 2022. Voluntary Sustainability Standards in International Trade. Available at: https://unctad.org/publication/voluntary-sustainability-standards-international-trade

[iii] UNFSS. 2022.Voluntary Sustainability Standards. Sustainability Agenda and Developing Countries: Opportunities and Challenges. Available at: https://unfss.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/UNFSS-5th-Report_14Oct2022_rev.pdf

[iv] Ibid (UNFSS, 2022).

[v] Tea and Coffee Trade Journal. 2025. Kenya suspends Rainforest Alliance certification for tea. Available at: https://www.teaandcoffee.net/blog/36936/kenya-suspends-rainforest-alliance-certification-for-tea/

[vi] UNEP/AMCEN/12/9. 2008. African Ministerial Conference on the Environment Johannesburg Declaration on the Environment for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.arso-oran.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/12thAMCEN_Declaration.pdf

[vii] This includes openness, transparency, impartiality, effectiveness and relevance, coherence, consensus and development dimension.

![[Blog] One Size Fits None: How Africa is Redefining Sustainability Standards on Its Own Terms](https://uneca.org/sites/default/files/styles/slider_image/public/storyimages/shutterstock_2060148593_1920x640.jpg?itok=EtcidMQO)